animal health consulting

Hendra: why not just go ahead and vaccinate?

Christine King BVSc, MANZCVS (equine), MVetClinStud

Table of Contents

Risks

Benefits

vaccine field study

Benefits: field study

A field study of Hendra virus (HeV) vaccine effectiveness was published in 2018. The stated goal was "[t]o determine the antibody responses to a commercial Hendra virus vaccine (Equivac® HeV) in a field environment." In this context, field means real-world conditions of use, not paddock or pasture.

The study used the research/teaching herd belonging to the James Cook University College of Public Health, Medicine, and Veterinary Sciences in Townsville, Queensland. Because horses are always entering and leaving institutional herds like this one for various reasons, not all of the horses completed the full vaccination program or were available for the entire 21/2-year study period.

Of the 61 horses in the herd when the study began, 57 horses received the first two doses of the vaccine protocol; 38 horses also received the third dose; but only 29 horses were still in the study by the time the first annual booster rolled around, and only 26 horses were available at the second annual booster.

The horses ranged in age from 2 years to 28 years, with an average age of 13–14 years. Most (49 horses) were Thoroughbreds; the rest were Standardbreds, Quarter Horses, or stock horses. There were no ponies, Miniature Horses, or draft breeds in the study group. Most (52 horses) were mares; the rest were geldings (8 horses) and 1 stallion.

Vaccination in this study followed the currently recommended protocol: 2 doses, given 3–6 weeks apart, followed by a third dose 6 months after the second; then a single booster every 12 months.

Blood samples for measurement of HeV antibody titres were collected immediately before and for variable periods after each dose of the vaccine was given. The horses were also monitored for any signs of adverse effects throughout the study.

Let's get that last item out of the way first.

Adverse effects

The goal of this study was to document HeV antibody titres in response to the currently recommended vaccination protocol. It was not a vaccine safety study, so reporting on adverse effects in this group of horses was scant.

In all, 206 doses of the HeV vaccine were administered during the study. According to the authors, "No local or systemic reactions attributable to vaccination were observed during this study and no adverse events following immunisation were recorded." That is consistent with the official reports of adverse events.

But note that the word attributable is doing some rather heavy lifting in that quote. (In case you skipped it, adverse effects associated with the HeV vaccine and under-reporting of adverse effects of vaccines in general are discussed under Risks: the vaccine.)

With fewer than 60 horses receiving the first dose of the vaccine, and only 26 horses making it all the way to the fifth dose (second annual booster), I don't think we can make very much of this finding.

Now to the meat of this study: HeV antibody titres.

HeV antibody titres

In most of the horses in this study, the recommended vaccination protocol induced HeV antibody titres that can be expected to be protective in the face of viral challenge.

As a reminder, the experimental vaccine challenge study showed that titres as low as 16–32 protected the horses from illness and prevented viral shedding in body fluids after HeV exposure through the natural route of infection (nose and mouth).

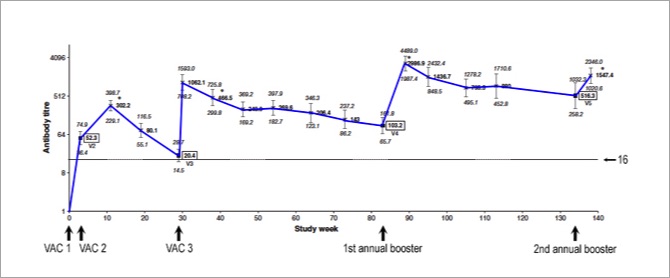

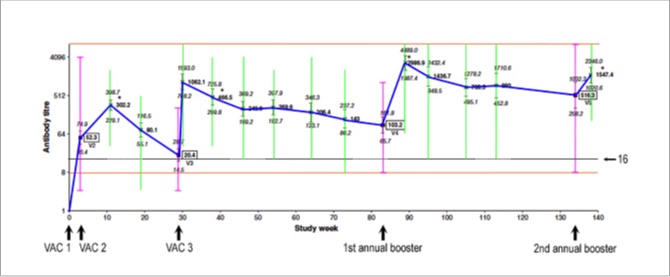

Below is a graph with the average titres at each time point connected by a blue line. The horizontal line running through the graph indicates a titre of 16.

For the scientists, the individual points are geometric means and the little vertical bars represent their 95% confidence intervals, with a log2 scale on the y axis.

Even the first dose of the primary series (VAC 1) induced a measurable antibody response in most horses. By the time the second dose (VAC 2) was due (3–6 weeks after the first), the average titre was already 52 — before the second dose was given.

We then see a bump up to an average titre of 302 around 8 weeks after the second dose (VAC 2). The average titre was probably even higher than that shortly after VAC 2, but the horses weren't retested until 8 weeks (± 2 weeks) after the second dose.

After the first dose, the average titre remained well above 16 at all time points except right before the 6-month booster (VAC 3), when the average titre had dropped to 20. So, this study indicates that the booster given 6 months after the second dose is pretty important in most horses. Or is it?

Look what happens right after the third dose (VAC 3): within 1 week, the average titre shoots up to 1,062.

The presumption is that average titres were set to drop below the threshold of 16, so the third dose was necessary to kick them back up again. But a drop in titre does not mean a drop in protection; it simply indicates a drop in circulating antibody, which is only one component of the body's complex of immune responses.

As I discussed on the previous page, that 'threshold' (titre of 16) is not based on very much, and may be higher than it needs to be. It's based on the fact that 16 was the lowest titre challenged; it is likely not the lowest titre that is protective under real-world conditions.

Clearly, the average horse with pre-existing immunity (in this study, from the first 2 vaccine doses) has the ability to rapidly produce a lot more antibody when challenged.

But then things get really interesting.

The study ended 4 weeks after the second annual booster. Notice that the average titres remained high after the 6-month booster (VAC 3), and they increased even further after the first annual booster, but there was not much of a bump after the second annual booster.

That second annual booster appears not to have been needed in most horses. One could even question the need for the first annual booster in the average horse, based on this study.

Are we wasting money and increasing the risk of adverse effects by giving annual boosters to every horse?

Perhaps we could be HeV antibody testing instead of automatically boostering according to the manufacturer's schedule. (More on HeV antibody testing later in the series.)

Here's why:

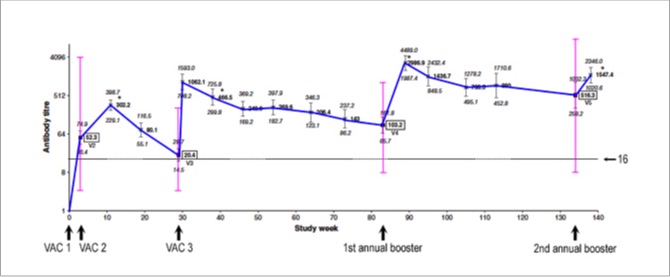

Below is the same graph with the range of titres (minimum to maximum) among individual horses, in pink, overlaid on the averages. This graph shows the range of titres immediately before each vaccine dose was given...

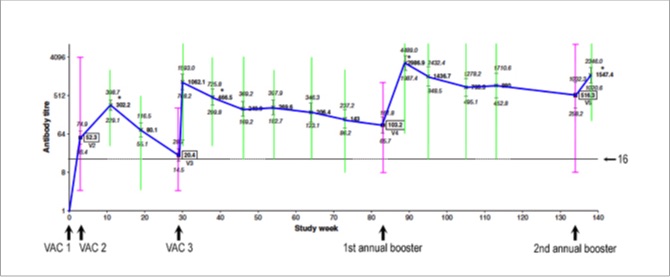

... and the graph below also shows, in green, the range of titres among individual horses for all of the test days after each vaccine dose was given...

Lastly, here is the same graph with the upper and lower limits of the assay shown as horizontal orange lines...

The upper limit was 8,192 and the lower limit was 8. Any values above this range were recorded as 8,192. How high they actually went, we don't know. But as I'll discuss a little later, titres as high as 32,768 were reported in a recent real-world study of HeV antibody titres in privately owned horses.

Any values below this range were recorded as 'undetectable', even though the horse had been vaccinated. In vaccine science, these individuals are called "poor responders" or "nonresponders." They do have some antibodies in their blood and, when appropriate studies are done, they have good cell-mediated immunity, including immunological memory. They simply don't have high circulating levels of antibody.

The reason these other lines (pink, green, and orange) are important is because the higher the titre, the longer it takes to fall below what we currently understand is a protective level. Immunologically speaking, boosters can be delayed in horses with high titres, and some of these horses had really high titres — literally, off-the-scale high!

One might even argue that boosters should be delayed in horses with high titres because vaccine reactions may be more likely in those individuals.

By the same token, a titre of less than 16 doesn't necessarily mean inadequate protection. As I noted, the average titre shot up from 20 to 1,064 within 1 week of receiving the booster dose at VAC 3.

In the 2018 study of diagnostic methods I've mentioned a couple of times, one naturally infected horse went from having a titre of less than 2 to a titre of 64 in 1 week.

The interval between viral exposure and first signs of infection, or the incubation period, for HeV is reported to be 5–7 days under experimental conditions and 5–16 days with natural exposure.

Clearly, it is possible for a horse with a low or undetectable titre to significantly ramp up HeV antibody production within that timeframe. It bears repeating that serum antibody titres are only one measure of a horse's immunity to HeV, and not necessarily the most important one; just the most easily measured one.

Horses with low titres

The authors don't tell us whether the same horses consistently had low titres, but based on research in other animals, that is most likely the case.

So, how many horses in this study had 'undetectable' HeV antibodies (titres of less than 8)?

At the start of the study, before the first vaccine (VAC 1) had been given, none of horses had detectable HeV antibodies. None had been vaccinated against HeV before the study began, and evidently none had recently been exposed to HeV either.

After the first dose, immediately before the second (VAC 2) was given, only 3 of 57 horses (5%) had undetectable antibodies. Put another way, antibodies were detected (titre of 8 or higher) in 95% of horses after the first dose.

After the second dose, immediately before the third (VAC 3) was given, 3 of 38 horses (8%) had undetectable antibodies. Were these the same 3 horses who had undetectable antibodies after the first vaccine? The authors don't say, but most likely so. The apparently higher percentage of "nonresponders" at this timepoint is misleading because it doesn't take into account the fact that 19 horses had been removed from the study by this point.

In university research/teaching herds, the horses are often used for multiple purposes, so this is neither a surprise nor an indictment. It is, however, a nagging problem with this study, as even more horses were removed ("dropped out" in clinical trial parlance) before the study ended.

Third dose (6-month booster)

After the third dose (VAC 3), given 6 months after the second dose, all horses had detectable antibodies (titre of 8 or higher) on every sampling day thereafter.

One could say that this proves the third dose is necessary to ensure that all horses respond appropriately to the primary vaccination series.

However, it could instead be argued that the dramatic response to this third dose indicates that it may not have been necessary at all, that all of the horses still in the study at the third dose had good cell memory and they mounted a vigorous antibody response to challenge (in this case, t0 the HeV surface protein in the vaccine).

First annual booster

By the time the first annual booster was due, titres had decreased in 21 of the 29 horses (72%) still in the study, but they remained 32 or higher in 26 of the 29 horses (90%).

All 29 horses had a significant rise in titre after this booster, "consistent with reactivation of a secondary immune response." (That's activation of immunological memory.)

But with an average pre-booster titre of 103 (it ranged from 8 to 1,024) and 90% of horses in this group having pre-booster titres of at least 32, was this booster really necessary in most horses? Can it be delayed in many, or even in most, horses?

If HeV titre testing was more affordable, we would be able to answer both questions definitively for each individual horse. Until then, the data from this study indicate that the answers to these questions are no, annual boosters do not appear to be necessary, and yes, apparently they can be delayed in many, and perhaps even in most, horses.

Based on the rate of decline in average titre following the third dose (VAC 3), the average horse (blue line) in this study would not have needed another booster until 18 months to 2 years after the third dose.

Things get even more interesting with the second annual booster...

Second annual booster

At the second annual booster, titres had decreased in only 12 of the 26 horses (46%) still in the study. In other words, titres had remained largely unchanged in 54% of horses.

It's worth noting, though, that in this study an 'increase' or 'decrease' in titre required a change of more than two steps: "When evaluating the rise and fall of antibody titres within individual horses, an increase or decrease in titre was considered to have occurred when there was a difference of more than two doubling dilutions between the two test results."

Put more simply, 25 of the 26 horses (96%) still had titres of 32 or higher when the second annual booster was due.

Most interestingly, only 5 of those 26 horses (19%) had a rise in titre after their second annual booster. Post-booster titres were unchanged in the other 21 horses (81%).

"Statistically, there was no significant rise in mean antibody titre in response to V5 [second annual booster] compared with after V4 [first annual booster]. In fact, a slightly lower mean titre was recorded (P = 0.0007)."

Now, isn't that interesting: not only was the second annual booster unnecessary, it was unproductive in ~ 80% of horses.

Titre decay study

I've already mentioned a 2021 study which examined the HeV antibody titres from 332 privately-owned horses. It, too, is a field study of sorts because it uses real-world data: blood samples from clients' horses, submitted to the lab by equine vets for the purpose of determining the horse's HeV antibody titre.

The researchers separated the results into two groups: the 27 horses who'd received only 1 or 2 doses of HeV vaccine (Primer group) and the 305 horses who'd received 3 or more doses (Booster group, who'd received between 3 and 12 doses in total).

The lower limit of measurement in this study was a titre of 4. Below that, the horse was considered "negative," even though all horses in the study had been given at least one dose of HeV vaccine, so all would have had at least some HeV antibody in their blood. Inexplicably, this study used a protective threshold of between 32 and 64. (Why so high? I don't know. It's not based on any data I'm aware of.)

This study presents perhaps the most interesting data on duration of immunity for the HeV vaccine, and possibly the most compelling argument against rigid adherence to the currently recommended vaccination protocol, including annual boosters, no exceptions, no deviations, no delays.

In the Primer group (horses who'd received only 1 or 2 doses of HeV vaccine), the median titre was 32. The middle 50% of the group had titres between 16 and 128. And while 3 horses had titres below 4 ("negative" in this study), another 3 horses had titres of 1,024 to 4,096.

But here's the most interesting bit: the interval between their last vaccine dose and titre testing ranged from 1,327 to 2,393 days — or 3.6 to 6.6 years.

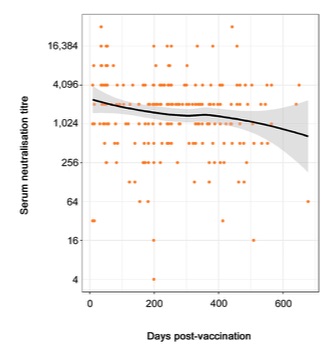

In the Booster group (horses who'd received 3 or more doses of HeV vaccine), there were enough horses that the researchers could plot the decline in titres over time and create a model of what we can expect in the general horse population:

(I changed the scale on the y axis from log2 to actual titre values, to make it easier to understand.)

The orange dots are the actual titres for the horses in this group. Titres ranged from 4 (1 horse) to 32,768 (2 horses). They are plotted according to the number of days since the horse's last HeV vaccine dose.

The black line is the 'line of best fit' which best represents the decline in titres over time in this group of horses.

The grey zone either side is the 95% confidence interval. Based on these data, we can expect, with 95% confidence, that the average values for the general horse population will fall somewhere within that grey zone, if not exactly along the black line itself.

Even though the grey zone flares out beyond 600 days post-vaccination, it still predicts that the average titre remains well above the protective threshold for close to 2 years after the last dose of HeV vaccine.

The grey zone flares out at the far end because there were too few data points out there for greater predictability.

The researchers repeated this plot after separating the horses into two subgroups: those who'd received 3 to 6 doses of vaccine (178 horses) and those who'd received 7 or more (up to 12) doses (127 horses). They used a linear model which straightened the somewhat curved black line in the graph above.

The only difference between these subgroups was that the average titre at the start (day 0) was much higher in the group who'd received 7+ doses: it was a little over 1,024 in the 3–6 dose group and just under 4,096 in the 7+ dose group. In the graph above, which includes all 305 horses who'd received 3 or more doses, the average value at day 0 was a little over 2,048.

Importantly, the slope of the black line didn't differ between subgroups, nor did its grey zone, indicating that HeV titre 'decay' is fairly consistent over time, regardless of its starting point.

In other words, no matter how high or low the titre is shortly after vaccination, it decreases over time at a fairly consistent and predictable rate, unless the horse is boostered again or is exposed to HeV in a natural setting.

We also see this in the field study that is the main focus of this page: there is a gradual decline in titre between the third dose (VAC 3) and the first annual booster, and between the first and second annual boosters.

Both field studies also show that average titres remain well above the threshold considered to be protective for far longer than the current, rigid vaccination schedule suggests.

Lessons from other species

Immunological studies in dogs and cats have resulted in sweeping changes to the recommended vaccination schedules, particularly in regard to booster intervals.

For example, in adult dogs it is now recommended that boosters for the core vaccines (distemper, hepatitis, parvo, and parainfluenza viruses) be spaced at least 3 years apart, rather than the customary annual boosters.

The guidelines also state that "[m]easuring antibody levels (quantitative or qualitative)* provides a reasonable assessment of protective immunity against CDV [canine distemper virus], CPV [canine parvovirus], and CAV2 [canine adenovirus type 2, which cross-protects against canine infectious hepatitis virus]."

* Quantitative measurement of the antibody level means titre testing, which reports an actual value or quantity. Qualitative measurement includes tests such as ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), which may report results only as positive, negative, or inconclusive.

Similar recommendations are made for adult cats: boosters at least 3 years apart.

It's unwise to extrapolate directly from one species to another, such as from dogs to horses, without good studies that show relevant similarities. But comparable research in horses hasn't even been done yet. It's high time it was — starting, perhaps with HeV.

Further thoughts

What if, instead of annual boosters, we started doing annual HeV antibody testing.

In my considered opinion, it would be better medicine to test all at-risk horses and booster only those who need it (e.g., those with negative HeV ELISA results or undetectable titres) rather than giving annual boosters to every horse, whether they need it or not. There may even be better uptake of the vaccine by horse owners if we took this approach.

The results of regular HeV antibody testing would also resolve the problem of vets not wanting to treat horses and equine hospitals and equestrian facilities/events not allowing entry of horses who are not "current" on their HeV vaccination according to Zoetis.

© Christine M. King, 2021, 2022. All rights reserved.

Last updated 17 June 2022.

to article main page